Great expectations

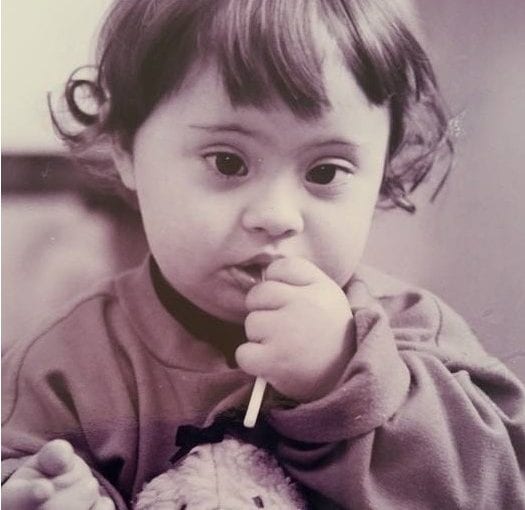

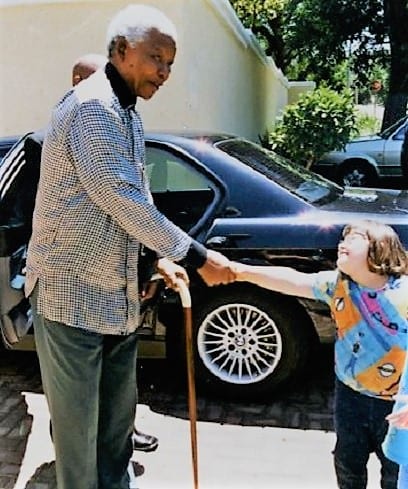

On Saturday the 23rd of April 1994, 3 days before our first free democratic elections, my Takara (Tiks as she’s affectionately known) was born. I was 23. Because she was prem, they whisked her off and 4 hours later brought her through to the ward where my mom and I were waiting. I wasn’t quite prepared for what followed. When I looked down at the tiny face, my heart skipped a beat, my stomach went into a knot and I heard myself say, “Mom, there’s something wrong with her! She ‘look “normal. Look at her face, she looks “mongoloid”. This is a term I would never use today, knowing what I do about Down Syndrome. My mom reassured me her ‘litty eyes’ were due to pressure in the birthday canal and they’d normalise over time. I wasn’t convinced.

A rude awakening

The next morning, lying in my hospital bed, in a ward of 8 other moms, they had closed my curtains and I overheard the paediatrician say to the nurse that they were sending for chromosome tests in the morning. My heart sank and I knew in that instant; my fears of the previous night were becoming a reality.

“In that moment, I knew I was the OTHER.”

The doctor, being a medical chap, broke the news to me in a matter of fact way. They suspected she had Down Syndrome but needed to run the relevant tests to be certain. The problem with an open ward is that even if you try to be quiet, other patients can still hear. The nurses, maybe for my own benefit, possibly to spare the other moms, had arranged me a private room and as they wheeled me out, the usually bustling ward was deathly quiet and the silence palpable. In that moment, I knew I was the “other” and the one with the handicapped baby, the one people felt sorry for and embarrassed in front of.

How it plays out

The next three days in hospital were not only the loneliest I’d ever experienced, but the sense of and was so strong it seemed to envelop me in its dark net with every interaction. To illustrate what I mean, each time I walked to the nursery, I’d pass the nurses station and they drop their voices and smile in an awkward, sympathetic way. A sense of seriousness seemed to pervade every visit. I could feel people’s discomfort, no one knew what to say. One friend heard and didn’t contact me for over 18 years. Later, an uncle advised I should put her in a home and forget about her (needless to say he was struck off the Christmas card list). I was painfully aware of people’s reactions when they’d walk up to the pram or cot and look inside. And every new encounter started the cycle of othering all over again.

The many faces of othering

And so this sense of being othered became part of our lives. Over the years, we’ve experienced kids pointing and staring, teenagers laughing and making rude jokes, adults speaking to me and not her when asking her name, shop assistants ignoring her in line and serving the person behind her, adults whispering about her in queues, waiters talking about her because they think I can’t understand if they speak in vernac. Sometimes the othering comes in the guise of kindness where people assume she can’t do things and so take away her rights or options to even try by doing it for her. We’ve become accustomed to the othering now and we’ve learned to manage it with more grace and compassion and with tolerance and understanding, particularly as we mature.

We’ve all been victims of othering

The truth is, all people experience being the outcast, the unacceptable one, the odd person out at some point. If we are women, we feel it when we enter a men’s only club, or are the only females in a board meeting. Black people live with this yoke continuously and hence movements like black lives matter. My gay son, like many gay people, experienced this at school when a kid called him a stupid fag. Old people describe this when they attend parties or functions and no one speaks to them because of their age. Asian people have felt this with the COVID 19 outbreak and witnessing people’s reactions to them. Of course we may argue that this is part of the human condition. Yes, it is. However, it’s part of the baser side of the human condition. It’s for that very reason, we should aim to rise above it.

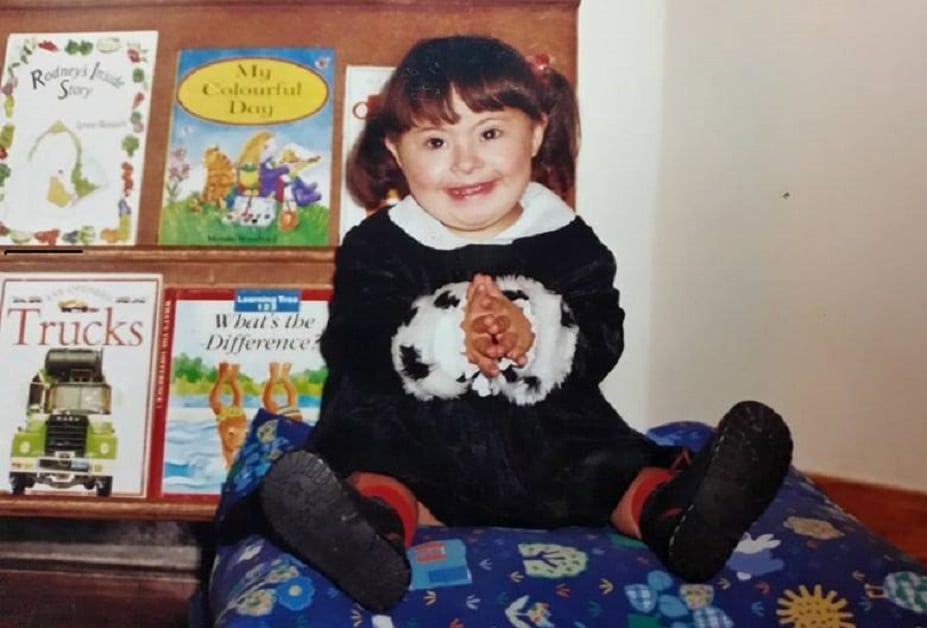

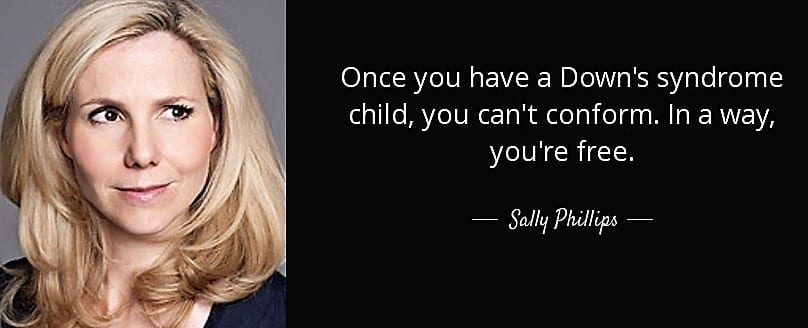

We’re more than our labels

Of course, as the mom of an intellectually disabled person, I know people will stare, assume, judge. They struggle to connect, to or to see her for who and what she is beyond her disability. She’s so much more than her label and she is just differently-abled. In our world Takara is our Tiks, a funny, quirky, cheeky, food-loving, creative and sometimes naughty member of our family. She’s great at washing dishes, remembering names, being the banker in Monopoly and recognising songs. She likes handsome boys and has a mad crush on Harry Styles, she’s kind and generous, remembers birthdays and she’s damn funny too. What a shame some people only see the 21 chromosomes before all that!

Othering can be subtle

Incidentally, othering doesn’t have to be extreme to impact people. This stuff plays out in families, the workplace, friendship circles. It may be as simple as I’m the extrovert in a group who is more introverted. Perhaps I have a more intuitive, creative way of processing information but my colleagues are more factual and practical. When we other someone we make it OK to treat them as “less than”. We use it to justify our bad behaviour, our lack of compassion and narrow mindedness. In fact, it’s the biggest obstacle to real tolerance and diversity.

“When we other someone, we make it ok to treat them as – less than.”

Othering must fall

What this has taught me is that the world doesn’t need more labels. We don’t need more others – we need more us. We need more we – less them, more community and less tribe. Tolerance, understanding, compassion are no longer nice to have. And if we want to build sustainable companies, happy families, thriving communities, a sustainable world where we can contribute and feel we belong, we can’t wait in the shadows. We can’t leave it up to some CEO, religious leader, community elder or politician to make the first move.

Be the change

We have to start with ourselves. Start with YOU! Here are some easy steps:

- First start by examining your judgement and stereotypes – maybe it’s about a work colleague, a partner, a manager, a staff member. Consider what these beliefs shut down.

- Examine the narrow views and perspectives you have about other groups, personality styles, religions, abilities, sexual preferences. Find the 1 thing in common you share and build from there.

- Build your compassion and curiosity. For the most part, you’ll be surprised at the beautiful lessons that come from a few well-intended questions. This is at the heart of real tolerance and diversity.

- And when you find yourself othering, catch it in that moment and make a different choice.

- If you’re on the receiving end, make it your business to educate gently. Be the one who extends the smile and hand of friendship.

My challenge to you is simple – look for the person behind the label. Next time you see a disabled person, smile and say hello. Teach your children to do the same. Because in the words of Robert Hensel,”There is no greater disability in society, than the inability to see people as more.”

#dontdismyability #dignityforall #readywillingandable #differentlyabled #otheringmustfall

Candida di Giandomenico is the founder of Thinck, a boutique training and development organisation. They offer bespoke solutions to improve your business and your life. She is the mom of 3. Takara, her oldest child was born with Down Syndrome and is a source of inspiration and ongoing learning. She has a keen interest in assisting leaders, teams and customer facing employees to work more effectively by understanding themselves and others more deeply. Her mission is twofold: firstly, to help businesses prosper by bringing more humanity to the workplace and secondly for individuals to master the art of being the best versions of themselves.

Email Thinck at hello@thinck.co.za